Norah Ruth Amstutz Light of a Potter's Spirit

Annie Dillard (Moth Detail)

Enter an artist’s studio and allow creativity to welcome you.

By Jan Wiezorek

That’s what you do when you meet potter Norah Ruth Amstutz from South Bend, Indiana. She serves you tea and pours it from her own handmade teapot into a cup she formed by hand, perfect for small sips of her own brand of artistry.

Here, in a converted garage behind her home, glowing hanging lanterns light a spirit that overwhelms you. Colorful urns appear to twist into textured leaves, faces, and blooming poppies and peonies. Art Nouveau-inspired designs bubble into forms and move into undulating organic shapes.

bell hooks

William Morris (Weaver Detail)

Her work employs language that shares inspiring messages. Time here in this studio becomes its own sound—like a rain stick tucked inside an hourglass. The space is peaceful as spirit, as visual as a gallery, and as personal as reading stories by lamplight.

All this and more comes from the creative vision of Amstutz, a 28-year-old University of Notre Dame 2025 Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art graduate, who recently won Best of Show at the 47th Elkhart Juried Regional at the Midwest Museum of American Art (MMAA) in Elkhart, Indiana. Her porcelain titled Evacuation impressed MMAA’s judges with its “carved” illustrative, three-dimensional surface containing folk art and narrative. Also, Amstutz received MMAA’s Jennifer Abrell and Dr. Gordon Hughes Purchase Award in 2025 for her porcelain titled Trickle Down. In 2024, she won Best Ceramic in the Elkhart Juried Regional and was featured as an emerging artist by Ceramics Monthly magazine.

Flask of Perpetuity

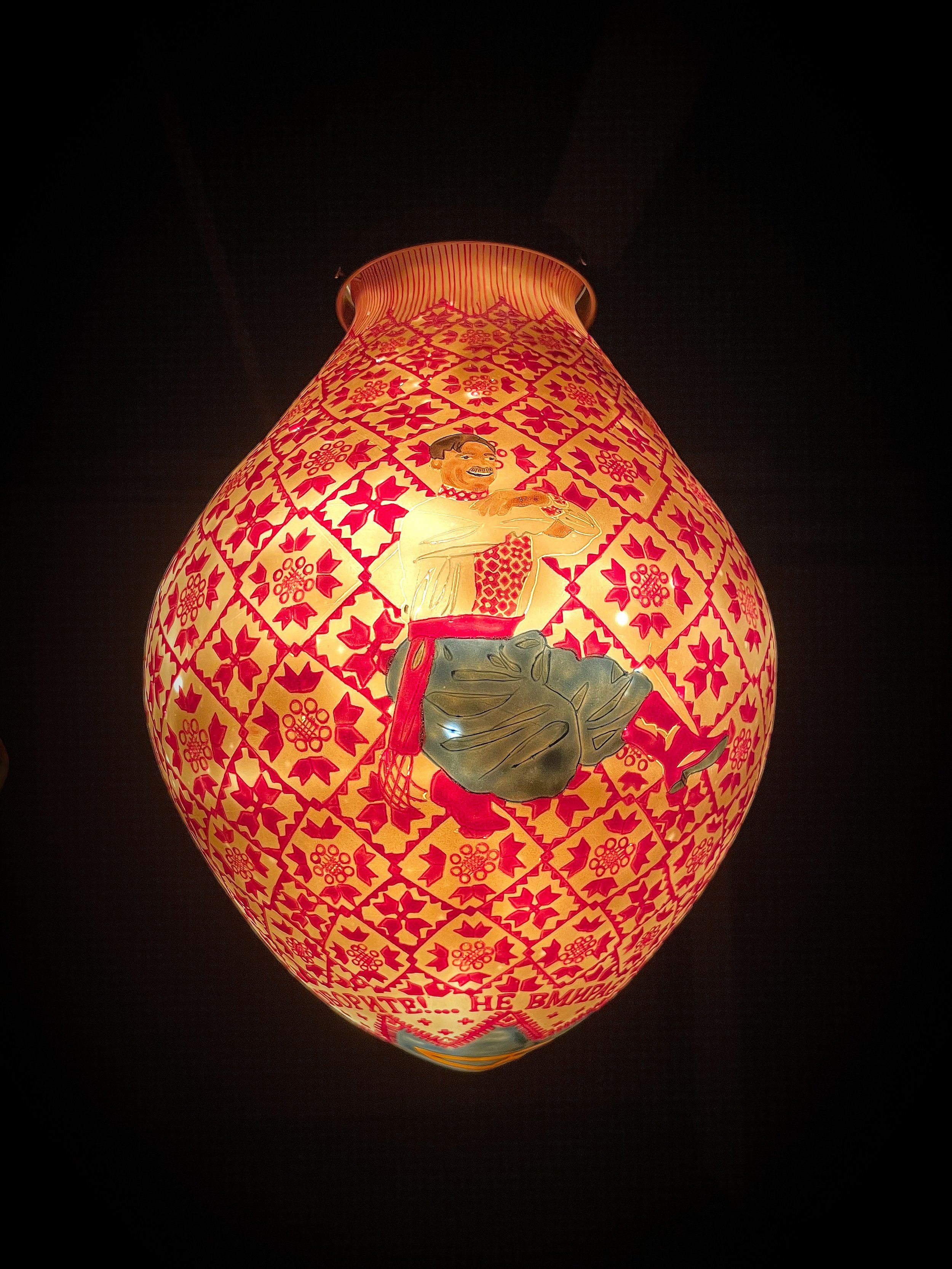

Amstutz’s spring 2025 Notre Dame thesis project was an exhibition titled To Be Certain of the Dawn—consisting of twelve lanterns, each devoted to an historical person “who contributed to a moment of consciousness-raising.” The lanterns contain portraits, floral images, stories told as visual scenes, and quotations. The lighted lanterns, about two feet high, hang from the ceiling and are as colorfully captivating as a chandelier or a lamp suspended from a church ceiling or a grand theatrical space.

One lantern is a homage to artist and designer William Morris and the craftspeople of art, such as weavers and potters. The lantern includes the sentence: “Art has remembered the people because they created.” The leafy images break away to reveal Goshen, Indiana, potter Dick Lehman, an elder artist in that community. Amstutz says she feels she is part of a “lineage of potters” that includes Lehman.

Smokescreen

For seven years after high school while living in Goshen, Amstutz worked as a studio assistant at potter Mark Goertzen’s studio, which Goertzen purchased from Lehman. Goertzen “gave me space to make mistakes and to find my voice,” she says. “I learned to throw on the wheel, handle clay and glaze, manage customer service, run the kilns, and make important social connections.”

Seeds of Time

After graduating from Goshen College with a Bachelor of Arts in Studio Art and English, the University of Notre Dame invited Amstutz to join its Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art program. There, she focused on the visuals of the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movements, especially on the works of William Morris and M. P. Verneuil. Their work influences her own designs that include nature themes and visual movement. She says she attempts to create leaves and floral patterns that honor the rhythm of the natural world, as if you might stumble upon them while walking in nature. Amstutz is drawn to the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movements because they use natural motifs that are in direct protest to industrialization.

Joseph Campbell (Hero’s Journey Detail)

Born in Ukraine and moving with her parents at age three to Goshen, Amstutz believes her faith community—with congregants who were immigrants from various ex-Soviet countries—

helped to shape her artistic sensibilities early on. “I think of being forged in a crucible—going to public school with American kids and coming home and being steeped in Ukrainian culture that I was experiencing secondhand through the people who brought it here.” In one of her urns, she breaks away from the rhythmic floral pattern to show the impact of oppression. She tells this story using a simple, bare scene of families in the former Soviet Union waiting for food in a breadline.

In another of her lanterns, Amstutz features writer Joseph Campbell and the hero’s journey. Her approach here is a Chartres Cathedral rose window that she believes is an important image in Campbell’s writing. Her lantern uses the window concept. She says the fullness of the design can be imagined if the lantern were to be flattened out as a two-dimensional work. Striking colorful diamonds, circles, and lantern shapes are set against a black background. Each window corresponds to a station on the hero’s journey, which is linked to the modern-day struggle against climate emergency. Her lantern To Be Certain of the Dawn functions as a hagiography on one level, expressing the lives of figures Amstutz has come to adopt as spiritual mentors.

Norah Ruth Amstutz

A third lantern honors the poet bell hooks. The poet’s essays inspired Amstutz to focus on the myths surrounding love and the need to integrate love into community. The lantern incorporates hooks’s face and the words: “When we choose to love, we begin to move against domination and oppression.”

Amstutz is commissioned to create another urn that will incorporate a family’s photographs and William Morris-style patterns. And in another project she has devised an hourglass shape for pottery, which she fills with a mini rain stick. When you turn the piece over, the sound mimics rainfall. It’s another idea that brings nature and spirit into her artistry.

Reading the writings of major thinkers and researching images on the Internet are among the ways Amstutz generates new ideas that “click” with her and “fit the narrative” she desires. During her student days at Notre Dame, she visited various museums, including the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, a trip that enabled her to encounter Verneuil’s work, a “guiding light” for her own designs.

Telling the Bees

Amstutz believes she struggles in her art to bring the intended meaning to viewers. “I think there’s strong logic behind all the choices I make. But it doesn’t necessarily translate to the viewer. This is a problem I am always looking to resolve in my practice.”

Water Protectors vs. Brabeck-Letmathe (Side A)

She works daily in her own studio, where she uses a pottery wheel. The studio has a large worktable and ample space for shelving and storing liquid clay and molds. But she says her electric kiln has “no soul.” She finds the results are flat and lifeless, with little surprise in the finished piece. To compensate, she uses sgraffito techniques to scratch into the surface and to employ decorative detail. She prefers using a wood-burning kiln and has access to one when she needs it. There are three wood kilns in the region, with groups of potters who share the kiln space and the work involved in achieving the firing.

Amstutz sells her teapots, mugs, pots, pitchers, and other pottery at such venues as the Michiana Pottery Tour and Arts on the Millrace in Goshen. For more information about Amstutz’s art, visit norahruthpottery.com.

Taras Shevchenko (Hopak Detail)

Ursula LeGuin Lantern